|

The Shiba's body size and appearance

|

The domestic dog (Canis familiaris) ranges in body size and appearance more than any other mammal. The smallest dog in the world is the Chihuahua whose withers can be just 15 cm (5.9 in.) high; the largest breeds are the Great Dane and the Irish wolfhound whose withers can reach a height of more than 80 cm (31.5 in.) and 90 cm (35.4 in.), respectively. Of course, these differences in size have not developed by natural selection but by means of artificial breeding. This took place according to the trial and error method: small dogs were paired with still smaller dogs, large dogs with larger ones. The genetic biological backgrounds underlying the control of growth have been unknown until recently. An international team of researchers from the USA and England has now published the results of a specific study on this subject in the April 2007 issue of Science (picture) which brings light into this subject.[1]

In this study the genome of more than 3,000 dogs from 143 breeds has been analysed. The Japanese dogs were represented in this project by two breeds, the Shiba for the small dogs and the Akita for the group of larger dogs.

The domestic dog (Canis familiaris) ranges in body size and appearance more than any other mammal. The smallest dog in the world is the Chihuahua whose withers can be just 15 cm (5.9 in.) high; the largest breeds are the Great Dane and the Irish wolfhound whose withers can reach a height of more than 80 cm (31.5 in.) and 90 cm (35.4 in.), respectively. Of course, these differences in size have not developed by natural selection but by means of artificial breeding. This took place according to the trial and error method: small dogs were paired with still smaller dogs, large dogs with larger ones. The genetic biological backgrounds underlying the control of growth have been unknown until recently. An international team of researchers from the USA and England has now published the results of a specific study on this subject in the April 2007 issue of Science (picture) which brings light into this subject.[1]

In this study the genome of more than 3,000 dogs from 143 breeds has been analysed. The Japanese dogs were represented in this project by two breeds, the Shiba for the small dogs and the Akita for the group of larger dogs.

After extensive DNA analyses, the researchers found out that a haplotype, that is a particular sequence of genes, on chromosome 15 influences the size of a dog significantly. Within this haplotype, a mutation in the gene called igf1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) has been identified as a determinant for size. Due to studies both on animals and humans, the influence of IGF1 proteins in the blood serum on growth processes was already known. The researchers now detected that a variant of the igf1 gene is present almost exclusively in large dogs, whilst the other (mutated) variant is found only in small dogs. Therefore, the igf1 gene has a decisive influence on the dog’s body size.

Based on archaeological findings of canine remains, the scientists assume that the igf1 gene already existed in the formative phase of the domesticated dog approximately 12,000 to 15,000 years ago. Dogs accompanying humans on migration and trading routes spread it quickly over wide areas. By breeding and selection the gene was thereupon "anchored" in local populations. Certainly it was conducive to this development that smaller dogs in many respects had more advantages than larger dogs. They needed less food and fitted in better with confined housing conditions. Smaller dogs were also more suited to certain kinds of hunting that prevailed, for example, from ancient times in Japan such as the tracking down and flushing out of game.

In Japan, large dogs originally did not exist. The typical indigenous dog was “mostly red-coloured and medium-sized”, as stated in a Latin dissertation of a witness at the end of the 18th century.[2]

Japanese dogs stem, molecular-biologically seen, from dogs who immigrated from the Asian mainland in the Jomon and Yayoi Period (10,000 B.C. until 300 A.C.) along with the first settlers. These dogs are the common origin (Nobuo Shigehara) of all later Japanese breeds and transferred the igf1 gene to the archipelago. Comparing measurements in remains of Jomon dogs with those of dogs from later centuries prove that the descendants of the Jomon dogs retained a pretty constant size close to that of the present-day Shiba.[3]

Large dogs did not exist in Japan until the 14th century when so-called "foreign dogs" (kara inu or tôken) were imported. Since the beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate in the 17th century increasingly large dogs were imported from Europe and were used by the shogun and the samurai as a status symbol and for hunting larger game.[4]

At the time of the shogunate when stronger dogs for the popular dog fighting were being raised, the largest native Japanese breed, the Akita Inu, also emerged. Similarly the Tosa Fighting Dog (Tosa Inu) which goes back to the Shikoku was developed. Akita and Shikoku were bred by crossing native breeds with imported dogs from Holland. To meet the demand of European dogs, the capital of Edo, the present-day Tokyo, suddenly "abounded" with dog experts, as was picked up in the diaries of the Dutch trading post at Deshima in Nagasaki Bay.[5]

Dogs had been bred for hunting in Japan since ancient times. Especially cultivated was the hunt with falcons (takagari) that was a prerogative and sport of the tenno, later of the shogun and his lieges, the daimyô (see pictures). For this ruling class the breeding of dogs as part of falconry was carefully controlled; there was an honourable office for dog breeding (inukai gashira or inuhiki) which later became part of the Ministry of Hawking.[6]

The dogs had to be capable of keeping track of the game upon discovery until the hunter was on the spot with his falcon. In breeding, great importance was attached to this hunting quality, whereas there was no reason to modify the dog’s size.

For the common people in Japan hunting was prohibited by the government as well as by the doctrine of Buddhism and played no part for a long time. Around 1690 Engelbert Kaempfer, a German physician and naturalist working for the Dutch East Indian Company in Japan, noticed: "Greyhounds and water-dogs are not known; when hunting, for which there is not much opportunity, ordinary dogs are used."[7]

Not before the end of the shogunate in 1867 were the restrictions eased. The common people who were now able to hunt used a specific hunting dog, the Kari Inu. During this time also larger game (wild boar, deer) was hunted by professional hunters (matagi) using larger breeds such as the Kishu and Shikoku that were more suited for this purpose.

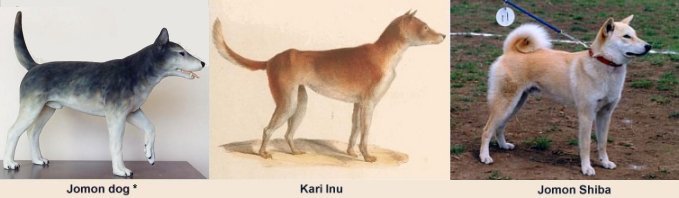

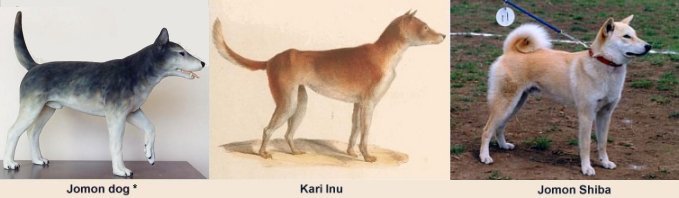

The exact origin of the Kari Inu (literally "hunting dog") is not known. The name was, as usual in Japan, a collective term for several dog populations that were used for hunting. Thanks to Philipp Franz von Siebold, another German physician and naturalist who lived from 1823 to 1830 in Japan while serving the Dutch, we have a good impression of the Kari Inu. As well as a description, Siebold’s Fauna Japonica (1842) contains a drawing of the Kari Inu. According to this, the Kari Inu resembled both the historical Jomon dog and the Shiba of today. The following pictures show the reconstruction of a Jomon dog, the Kari Inu from the Fauna Japonica and a current variety of the Shiba, the so-called Jomon Shiba:

* Courtesy of the Tobinodai Historical Park Museum, Funabashi-shi, Japan.

According to the description in the Fauna Japonica the Kari Inu was vivid and docile, had a svelte bone structure with a well shaped, slight head.[8]

In another work, Siebold furthermore mentions the pricked ears and the rolled tail as being characteristic.[9]

No specification is made by Siebold regarding the Kari Inu’s size. Therefore, I have researched Siebold's literary archive at the University of Bochum, Germany, and detected an unpublished manuscript entitled “Measurements of Japanese dogs” (Ms 13388 – see picture). In this manuscript, nothing is said about the type of the dogs, only the names are given. But as I see it the dogs measured can only have been the Kari Inu considered by Siebold to be the only native Japanese dog. A comparison of the measurements specified in the manuscript with those of a present-day Shiba shows that the Kari Inu was not much taller than the modern Shiba (forelegs 28.35 cm (11.61 in.) as opposed to 21 cm (8.26 in.) in the Shiba).[10]

However, Kari Inu and Shiba are alike not only in their physical appearance but have also the hunting instinct in common. Until the first half of the 20th century, the Shiba was used in the mountainous areas of Middle Japan (Shinshu, San-In, Mino) for hunting ducks (yobiyose-ryo) and pheasants (ageki-ryo). Finally, there is a further common trait of Kari Inu and Shiba. In another manuscript from the Siebold archive (Ms 16820) the Kari Inu is characterised as a "Wachthund (shuken)", i.e. guard dog – just as the Shiba who is known to be an "excellent watch dog"[11].

In conclusion, I am convinced that the present-day Shiba is a descendant from a local variety of the Kari Inu as Siebold has described him.

No specification is made by Siebold regarding the Kari Inu’s size. Therefore, I have researched Siebold's literary archive at the University of Bochum, Germany, and detected an unpublished manuscript entitled “Measurements of Japanese dogs” (Ms 13388 – see picture). In this manuscript, nothing is said about the type of the dogs, only the names are given. But as I see it the dogs measured can only have been the Kari Inu considered by Siebold to be the only native Japanese dog. A comparison of the measurements specified in the manuscript with those of a present-day Shiba shows that the Kari Inu was not much taller than the modern Shiba (forelegs 28.35 cm (11.61 in.) as opposed to 21 cm (8.26 in.) in the Shiba).[10]

However, Kari Inu and Shiba are alike not only in their physical appearance but have also the hunting instinct in common. Until the first half of the 20th century, the Shiba was used in the mountainous areas of Middle Japan (Shinshu, San-In, Mino) for hunting ducks (yobiyose-ryo) and pheasants (ageki-ryo). Finally, there is a further common trait of Kari Inu and Shiba. In another manuscript from the Siebold archive (Ms 16820) the Kari Inu is characterised as a "Wachthund (shuken)", i.e. guard dog – just as the Shiba who is known to be an "excellent watch dog"[11].

In conclusion, I am convinced that the present-day Shiba is a descendant from a local variety of the Kari Inu as Siebold has described him.

Notes

[1] Nathan B. Sutter, Carlos D. Bustamante, Kevin Chase, et. al.: A Single IGF1 Allele Is a Major Determinant of Small Size in Dogs, Science 316 (2007), pp. 112-115.

[2] Olaus Wernberg: Fauna Japonica, Uppsala 1822, p. 5: "colore plerumque rubro, communis est; mediocris magnitudinis". The real author of this dissertation was the well-respected Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg, pupil of the famous botanist Carl von Linné (Carolus Linnaeus) and later successor on Linné's chair at Uppsala University. Thunberg stayed in Japan from 1775 to 1776.

[3] Nobuo Shigehara, Hitomi Hongo: Ancient remains of Jomon dogs from Neolithic sites in Japan, in: Susan Janet Crockford (ed.): Dogs Through Time. An Archaeological Perspective, Oxford 2000, pp. 61-67; Michiko Chiba, Yuichi Tanabe, Takashi Tojo, Tsutomu Muraoka: Japanese Dogs. Akita, Shiba, and Other Breeds, Kodansha International, Tokyo, New York, London 2003, p. 62.

[4] Beatrice M. Bodart-Bailey: The Dog Shogun. The Personality and Policies of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, University of Hawai'i Press 2006, p. 132.

[5] Paul van der Velde, Rudolf Bachofner (eds.): The Deshima Diaries. Marginalia 1700-1740, Tokyo 1992, p. 276. Not only large dogs were in demand but also small ones. On the wish list of a Japanese sovereign (daimyô) from 1633 were "the largest dogs that can be obtained. The smallest pooches of all, which have artistic capabilities." Unpublished diaries (dagregisters) of the VOC, cited by Wolfgang Michel: Von Leipzig nach Japan. Der Chirurg und Handelsmann Caspar Schamberger (1623-1706), München 1999, p. 111. With such dogs apparently one could make an impression in Japan where only medium-sized dogs were usual.

[6] Beatrice M. Bodart-Bailey: The Laws of Compassion, Monumenta Nipponica 40/2 (1985), pp. 163-189.

[7] Engelbert Kaempfer: Geschichte und Beschreibung von Japan. Aus den Originalhandschriften des Verfassers hrsg. v. Christian Wilhelm Dohm, Lemgo 1777-79, vol. 1, p. 143. English translation: Beatrice M. Bodart-Bailey: Kaempfer’s Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed, University of Hawai’i Press 1999, p. 408.

[8] Ph. Fr. de Siebold: Fauna Japonica sive Descriptio animalium (...), Lugduni Batavorum (= Leiden) 1842, p. 37.

[9] Philipp Franz von Siebold: Nippon. Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan und dessen Neben- und Schutzländern Jezo mit den südlichen Kurilen, Sachalin, Korea und den Liukiu-Inseln, Würzburg/Leipzig 1897, vol. 2, p. 259.

[10] The manuscript is written in Dutch, except for the title which is in German. A publication is under way.

[11] Maureen Atkinson: The Complete Shiba Inu, Ringpress Books 1998, p. 10.

© Holger Funk 2007

Also published in Shiba World Vol. III 2007

The domestic dog (Canis familiaris) ranges in body size and appearance more than any other mammal. The smallest dog in the world is the Chihuahua whose withers can be just 15 cm (5.9 in.) high; the largest breeds are the Great Dane and the Irish wolfhound whose withers can reach a height of more than 80 cm (31.5 in.) and 90 cm (35.4 in.), respectively. Of course, these differences in size have not developed by natural selection but by means of artificial breeding. This took place according to the trial and error method: small dogs were paired with still smaller dogs, large dogs with larger ones. The genetic biological backgrounds underlying the control of growth have been unknown until recently. An international team of researchers from the USA and England has now published the results of a specific study on this subject in the April 2007 issue of Science (picture) which brings light into this subject.[1]

In this study the genome of more than 3,000 dogs from 143 breeds has been analysed. The Japanese dogs were represented in this project by two breeds, the Shiba for the small dogs and the Akita for the group of larger dogs.

The domestic dog (Canis familiaris) ranges in body size and appearance more than any other mammal. The smallest dog in the world is the Chihuahua whose withers can be just 15 cm (5.9 in.) high; the largest breeds are the Great Dane and the Irish wolfhound whose withers can reach a height of more than 80 cm (31.5 in.) and 90 cm (35.4 in.), respectively. Of course, these differences in size have not developed by natural selection but by means of artificial breeding. This took place according to the trial and error method: small dogs were paired with still smaller dogs, large dogs with larger ones. The genetic biological backgrounds underlying the control of growth have been unknown until recently. An international team of researchers from the USA and England has now published the results of a specific study on this subject in the April 2007 issue of Science (picture) which brings light into this subject.[1]

In this study the genome of more than 3,000 dogs from 143 breeds has been analysed. The Japanese dogs were represented in this project by two breeds, the Shiba for the small dogs and the Akita for the group of larger dogs.

No specification is made by Siebold regarding the Kari Inu’s size. Therefore, I have researched Siebold's literary archive at the University of Bochum, Germany, and detected an unpublished manuscript entitled “Measurements of Japanese dogs” (Ms 13388 – see picture). In this manuscript, nothing is said about the type of the dogs, only the names are given. But as I see it the dogs measured can only have been the Kari Inu considered by Siebold to be the only native Japanese dog. A comparison of the measurements specified in the manuscript with those of a present-day Shiba shows that the Kari Inu was not much taller than the modern Shiba (forelegs 28.35 cm (11.61 in.) as opposed to 21 cm (8.26 in.) in the Shiba).

No specification is made by Siebold regarding the Kari Inu’s size. Therefore, I have researched Siebold's literary archive at the University of Bochum, Germany, and detected an unpublished manuscript entitled “Measurements of Japanese dogs” (Ms 13388 – see picture). In this manuscript, nothing is said about the type of the dogs, only the names are given. But as I see it the dogs measured can only have been the Kari Inu considered by Siebold to be the only native Japanese dog. A comparison of the measurements specified in the manuscript with those of a present-day Shiba shows that the Kari Inu was not much taller than the modern Shiba (forelegs 28.35 cm (11.61 in.) as opposed to 21 cm (8.26 in.) in the Shiba).