|

The dog's DNA for the first time completely deciphered |

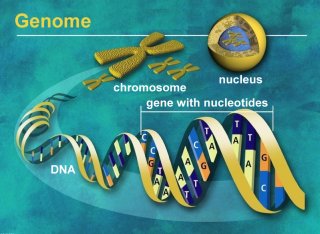

Some time ago a large number of scientists from all parts of the world joined together for a research project entitled "Dog Genome Sequencing Consortium". The researchers had made it their business to decipher the dog's genome, i.e. the chromosomes and the genes which are located in them (about 20.000). The technical term for this analysis is "sequencing" which means reading the base sequences (nucleotides) of the DNA. A total of 2.41 billion individual sequences had to be read, compared by means of special software and compiled in the correct order. This project was directed by the renowned Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard ("Broad" for short) in Cambridge, Massachusetts (USA). At beginning of December 2005 the long-awaited day arrived: in the journal Nature [1] the first complete decoding of the dog's DNA was published.

From the many new findings which this ambitious project produced we want to point out just three here which are generally understandable even for the non-professional. These regard

– the dog's evolution

– the identification of disease-causing genes

– "ancient" breeds in contrast to "modern" breeds

The dog's evolution

Thanks to the new Broad study as well as findings from former molecular-biological research the dog's evolution can be outlined pretty accurately. Accordingly the wild ancestor of the dog is the grey wolf which belongs to the large group of mammals called Carnivora ("meat eaters"). Approximately 40 million years ago a family of dog-like predators (Canidae) developed out of this group from which again about 15 million years ago foxes, wolves, jackals and other animals evolved. The closest relative of the grey wolf is the coyote, followed by the golden jackal, Ethiopian wolf, Asiatic wild dog (dhole) and African wild dog (hyaena).

| The phylogenetically closest relatives of the domestic dog (Canis familiaris) | ||

|  |

|

| Grey wolf (Canis lupus) | Coyote (Canis latrans) | Golden jackal (Canis aureus) |

|

|

|

| Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis) |

Asiatic wild dog (dhole) (Cuon alpinus) |

African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) |

At least 15.000 years ago (possibly earlier) the domestication of single wolves began and the domestic dog developed. His place of origin is in all likelihood Southeast Asia. In the company of man the domestic dog also colonised the New World via the Bering Straits, meaning that America's dogs are also descended from the domestic dog and are not – as believed for some time – of their own origin.

The study of the Broad researchers demonstrates furthermore that in the dog's history of development two population "bottlenecks" occurred. Such a situation happened in the early phase of domestication about 9.000 generations ago and again during the establishment of modern breeds about 50-100 generations ago, i.e. roughly during the 18th and 19th centuries. In both instances only very few individuals still existed so that inevitably inbreeding took place in the reproduction process. Furthermore the gene pool of some breeds diminished due to external influences such as wars and epidemic plagues.

One result of these bottlenecks is a still traceable "hardening" of the genetic structure including hereditary diseases, because, so to speak, "fresh blood" was lacking. A typical example for a current breed with bottleneck character is the Akita Inu which for this reason was analysed by the Broad researchers.

The identification of disease-causing genes

There are some hundred hereditary diseases known which are common to humans and dogs, the most common being cancer, epilepsy, allergies, auto-immune diseases (e.g. skin disorders such as sebaceous adenitis – spread in Akitas for a short time), blindness, deafness, eye cataract and heart diseases.

Besides these hereditary diseases common to humans and dogs, some less frequent diseases exist which have occurred only in single breeds, for example a certain kind of inherited renal cancer developed only in German Shepherd Dogs. Also the fatal storage disease gangliosidosis until now has been reported to have affected only the Shiba, and 7 further breeds.

As well as the bottleneck situations mentioned, breed regulations ("standards") such as the "Breed Barrier Rule" (formulated for the first time in the 19th century) play a part in causing hereditary diseases in dogs. The price for the variety of modern breeds by means of selective breeding is the conservation of certain hereditary traits whereby also negative dispositions and mutations are passed on. In extreme cases even a hereditary disease is ennobled as standard – as for example the hairlessness in naked dogs.

The exploration and identification of gene defects common to humans and dogs was the original target of the Broad project. Already there are so-called gene maps available in which disease-causing genes in dogs are registered and classified. Additionally there is a project at the University of Cambridge in England by the name of IDID (Inherited Diseases In Dogs) in which many hereditary diseases including the relevant scientific articles are listed. [2] This project is accessible for everybody via the internet; the required information can be found by searching either for the names of diseases or breeds.

The investigation of hereditary diseases in dogs very often acts as a model for the investigation of the same disease in humans. The scientists on the Broad project are confident that on the basis of the now decoded DNA, further studies with new findings will be published soon. This means that a substantial progress in diagnosis and therapy can be expected and improved breed programmes developed.

"Ancient" breeds in contrast to "modern" breeds

The scientists of the Broad project cooperated closely with the American Kennel Club (AKC) and many others breeder associations. An important question was which representative of the more than 400 breeds should be selected for the study. Ideally a breed assumed to have an especially homogeneous genetic disposition with as few mutations as possible was sought after. This could be only a relatively "modern", highly inbred breed. After checking 60 breeds finally the female Boxer dog Tasha (see picture) was chosen. For control reasons more than 30 further breeds, one coyote and four different wolf populations were included.

The scientists of the Broad project cooperated closely with the American Kennel Club (AKC) and many others breeder associations. An important question was which representative of the more than 400 breeds should be selected for the study. Ideally a breed assumed to have an especially homogeneous genetic disposition with as few mutations as possible was sought after. This could be only a relatively "modern", highly inbred breed. After checking 60 breeds finally the female Boxer dog Tasha (see picture) was chosen. For control reasons more than 30 further breeds, one coyote and four different wolf populations were included.

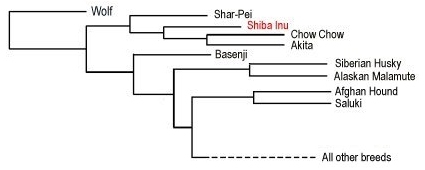

The Shiba was never a candidate for the genome analysis – not without good reason. Parallel to the Broad project another big study was made with members of the Broad project participating as well. In this study 414 dogs representing 85 breeds were investigated for the genetic relationship among breeds and for the genetic closeness to the grey wolf, the progenitor of the dog. [3] The researchers detected that the breeds could be divided into four groups ("clusters"), three "modern" and one "ancient" group. Only this "ancient" group shows a significant genetic closeness to the wolf whereas all breeds forming the three "modern" groups were irrelevant in this respect.

The "ancient" group includes only 9 different breeds from quite different parts of the world. In this group the Shar-Pei, the Basenji and the Shiba Inu showed the greatest genetic relationship to the wolf. In the following picture the whole context is graphically displayed:

The Shiba is one of the genetically closest relatives of the wolf – one must not be mislead by the external appearance, the phenotype. For this reason the Shiba did not qualify for the Broad project when a modern dog was sought after. The Shiba Inu and – as we know thanks to Japanese research – as well the Hokkaido Ken [4] belongs to the rare really original dog breeds.

| [1] | Kerstin Lindblad-Toh, Claire M. Wade et al.: Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog, Nature 438, December 2005, pp. 803-819. |

| [2] | Sargan, D. R.: IDID: inherited diseases in dogs: web-based information for canine inherited disease genetics, Mammalian Genome 15 (2004), pp. 503-506. |

| [3] | Heidi G. Parker, Lisa V. Kim et al.: Genetic Structure of the Purebred Domestic Dog, Science 304 (2004), pp. 1160-1164. |

| [4] | Yuichi Tanabe: Phylogenetic studies on the Japanese dogs, with emphasis on migration routes of the dogs, in: Japanese as a Member of the Asian and Pacific Populations, ed. Kazuro Hanihara, Kyoto 1992, pp. 160-173. |

© Holger Funk 2006

Translated and reprinted in Shiba Sanomat 1/2007 (Finland)